This post is about css with companion sections from a clojure perspective.

The high level goal of CSS is to produce a visually appealing website. Humans appreciate the design, but it's machines that set the rules so it pays to know the constraints and contracts. And as part of what makes something beautify is it's responsiveness and that means talking about optimizations.

Here are some rough categories that the over all discussion can be broken into:

However it's important to note that the high level concepts are simply that you want to minimize space (package size) and time (latency). But doing so never comes for free, typically costing either more human time or resources to achieve.

Minifing css is relatively straight forward. From google developers:

Minification refers to the process of removing unnecessary or redundant data without affecting how the resource is processed by the browser - e.g. code comments and formatting, removing unused code, using shorter variable and function names, and so on.

As an example we go from this human readable file:

html,

body {

height: 100%;

}

to this minimal file:

body,html{height:100%}

A tool should handle this for you. In the clojurescript world, say if your using shadow-cljs and your styles are inlined then this will happen as part of the minification of the application. If your using a css stylesheet, then you will need to use one of the various libraries out there. Such as asset-minifier or postCSS. You can read more about minification here.

This is very similar to dead code elimination, which in turn is related to the Halting Problem. Long story short, it's impossible to do perfectly. As this experience report highlights trying to do it manually can troublesome. The lesson here is that you need to prefer prevention over clean up.

How? The same techniques we practice in software development apply. Logic should be isolated, minimal and composed. Consider this example:

(defn some-componet

[:p {:style {:color "red"}}])

This style is part of the component, that means it will only render if the component renders. That's a good coupling because it's direct and private. No chance layers of indirection will cause un-needed styles will end up there. prefer ridged code, use indirection only when necessary. It also means the Google Closure Compiler has a chance to do dead code analysis.

But the story of this example doesn't stop here, we should note that were using what looks like to be an inline style. You might have a knee jerk reaction that this isn't good. But why? It's not an organizational issue, that hashmap is just clojure. It could be a variable. The historical reason for the pushback comes form another way to optimize which will cover in the cacheing section.

As explained here one way to do this is via media queries. This means the styles are still downloaded, but aren't blocking. Another opportunity to do this is through code splitting with reacts lazy load option which you can read about here. While this isn't specifically aimed at CSS sense your components might have local CSS in them, it's worth mentioning here.

Near last by far from least, is the topic of loading assets. Let's set the premise, this is fundamentally a business decision. e.g how important is the first load? Is it better to have fast content vs up to date content? As an engineer it's your job to bring these options to your teams attention in a easy to understand simplified form. With that in mind, let's talk about the trade offs at a high level and then talk about what knobs we have to turn.

The highlevel trade off is space vs time. What I mean by this is that if you send the user all the assets at once, it will take more time on initial load, but less time on subsequent actions on his part. A business much evaluate this choice, but typically it's good to minimize your first load. Another example would be caching. You could tell the browser to never validate if an asset was expired, this means there wont be a latency penalty to check.

Concerning Caching, I agree with the logic here that a sensible default is no cacheing. The goal is to make sure content is always fresh and to do that as quickly as possible. This relies on CDN's and telling your browser to always revalidate. If you can have a hot CDN cache near your user base, then i believe they can benefit from each other and share pages. You configure this functionality through the header:

Cache-Control: max-age=0,must-revalidate,public

;; or

Cache-Control: no-cache

However realize that this works best for moderately fast connections. Another option is to have immutable assets and to save them forever via:

Cache-Control: max-age=31536000,immutable

In order to make them immutable there are a couple options, but essential the files have to have unique names. While Shadow-cljs has built in support for hashing js modules and code splitting (which you should be doing!). It doesn't seem to give the same treatment to css style sheets, again this isn't an issue if everything is inlined.. Going this route means that any asset update will trigger a new re-fetch as where old assets will be cached by the browse. I believe this could be coupled with a load balancer redirect that always grabs the newest home/index.html and avoiding having to hash your index.

Those are some general strategies, but what about the actual controls for browser cacheing? Those are well covered here and here but come down to several controls on the request and response headers:

Practically speaking, the following Cache-Control configurations are a good start:

It's recommended to use the Etag over the last-modified because its more accurate. But how do we decide what should and shouldn't be cached? This SO question has a good answer.

Overall, the story about cacheing and loading doesn't change in clojurescript land.

This process, of inline styles is most important for the first page load, what some call "above the fold". The css in that first page load is refereed to a "critical", because users typically will leave a site that loads to flow especially at the start. Introductions are important. From Google:

For best performance, you may want to consider inlining the critical CSS directly into the HTML document. This eliminates additional roundtrips in the critical path and if done correctly can deliver a "one roundtrip" critical path length where only the HTML is a blocking resource.

Luckily there are tools to help do this such as discussed here. However i Have no doubt that this is a bit error prone. Additionally, next time you turn around there might be a way the browser can detect this with no intervention and your efforts have been wasted.

Please read this post that concludes that css classes are generally faster then inline styles mostly because of browser internals. That that difference is significant (30%) between the two, but probably negligible for the overall experience (~10ms).

This might be why the react docs have this to say: have this to day:

CSS classes are generally better for performance than inline styles.

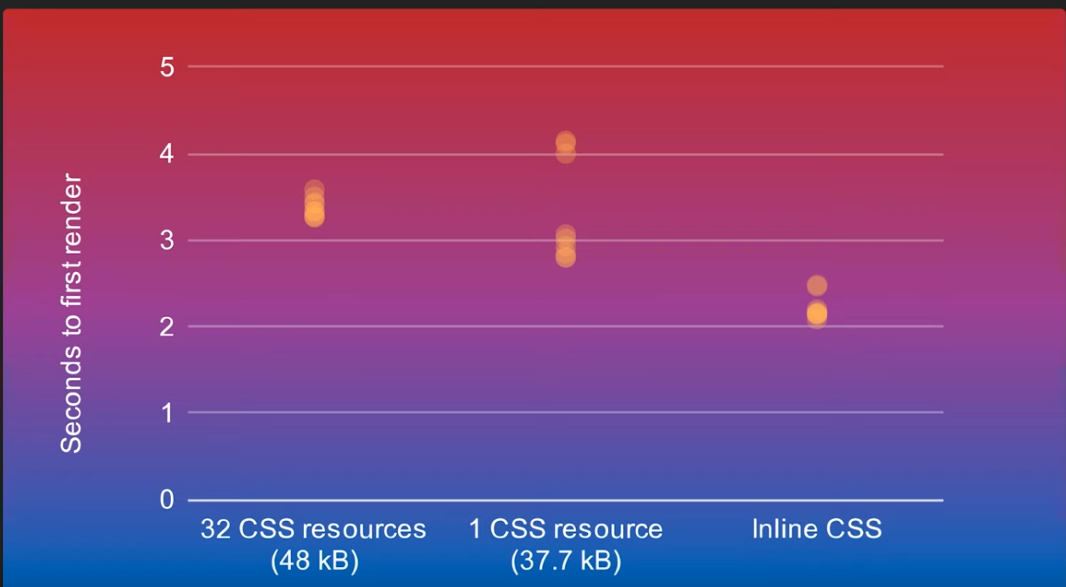

However, it's possible that this isn't true across browsers, and most importantly as is suggested by this Google Chrome Developer Representative inline css is on average faster because you end up with less bloated payloads. At 14:52

the real value of inlining is that you you don't have to architect what goes in what css file to try and figure out what you know how that will spread across your pages in an optimal way you can just serve what is needed by that page.

Here is a glimpse into the comparison from the video above:

This is great point and it really drives home what I have been saying. This word "inline" is all wrong, what were talking about is locality. About .css files being giant blobs of shared mutable state with unclear publishers and subscribers.

Here are some assorted readings that in aggregate were less helpful then the post above:

What I mean by organization of css is akin to "code quality" or "simple design". Which means, it's nearly impossible to talk about it in general! What to do then? Give up? Pick up a cargo cult methodology or framework that deals with orthogonal concerns and pretend it solves the issue? No. The hidden secret to architecture is to only setup structure where needed, motivate correctly, and then trust.

When we discuss organizing css we can think about it from two perspectives.

Let's first cover some basics of how styles are applied. Go ahead and read this on CSS Cascade and Inheritance. I think the only really interesting functionality here is inheritance. Luckily, it's an old topic. Inheritance is just a tree, the parent functionality flows to the children. That's useful. But it doesn't cover all cases. Sometimes two children with different parents have to share some functionality. That's why tree's are a subset of graphs and why being able to share styles outside Inheritance is useful and necessary.

The next big topic concerning the browser is Layout. Unfortunately, this topic (like all browser concerns) is constantly evolving as the browser adds new features. And you absolutely want to keep up to date with them as they will make doing your job easier, even if it means spending more time learning. Embrace the chaos! At the time of this writing you should be moving towards or using CSS Grid. I suggest watching and read everything written by Jen Simmons.

Given we understand the browser, it's api, and it's performance tradeoffs, how do we go about effectively running a business through the lens of css? That's a loaded question, the answer is obviously that it depends!

There are guiding principles though. Do you want team members to be generalists or specialists? If you pick generalists you should prepared to get less then perfect CSS, after all, they might decide that fiddling with that button is far less important then reducing the backed pipeline. Maybe you hope to have both by having architects and specialists? But what are the specialists going to work on when they have run out of things to work on effectively?

Let's move past the general uncertainty and focus on some area's I can speak on with some personal experience. Web development using Clojure. In this case, one organization choice that you could face is using stylesheets vs css-in-js. Luckily, the real choice here is based on how you want to structure your team. If you have dedicated designers, then stylesheets are likely a good separation of concern. But It might not exactly be stylesheets that your designers are using, but collaborative interface design tools like Figma which are at a higher level. However if you have chosen to higher mostly developers and tasked with with design and implementation , then you should invest in a tool like storybook or workspaces. Assuming your using react and/or clojurescript.

Earlier I said the real difference between CSS stylesheets and css-in-js was in team dynamics, that's because solutions like cljss allow you structure your html and css tries together using clojure:

(defkeyframes spin [from to]

{:from {:transform (str "rotate(" from "deg)")

:to {:transform (str "rotate(" to "deg)")}})

[:div {:style {:animation (str (spin 0 180) " 500ms ease infinite")}}]

And then they produce stylesheets! There is just one hiccup.

Because CSS is generated at compile-time it's not possible to compose styles as data, as you would normally do it in Clojure. At run-time, in ClojureScript, you'll get functions that inject generated CSS and give back a class name. Hence composition is possibly by combining together those class names.

This happens because were generating class names/strings

(defstyles margin-y {:margin-top 1}) ;; => "some-class"

(defstyles margin-x {:margin-bottom 2}) ;; => "some-other-class"

Now we have to do string concatenation of "some-class" and "some-other-class" if we want both. I think it would be a major improvement to overcome this limitation where ever possible (even if it meant using inline styles in some cases!).

The other problem is that by putting our CSS behind marcos (necessary to generate stylesheets). We no longer can no longer user cljs to compose style at runtime. I suspect you can work around this in most cases, but it will probably be something of a creative exercise. And the reason were doing this is because of performance that might not matter! So then, my tentative recommendation is to start with inline-styles, using a cljs-in-jss like tool. Then benchmark and adapt as needed. Luckily Reagent ships with everything you need. You can just use the style map:

(defn some-componet

[:p {:style {:color "red"}} "hi"])

And what about things you can't inline? Well just use a style tag

(defn some-componet

[:div

[:style "@media screen..."]

[:p {:style {:color "red"}} "hi"]])

At this point you might be a bit shell shocked, that after all this i'm recommending inline styles. But you shouldn't be and i'm not really. I'm recommending being direct and isolated as possible, because indirection can lead to confusion. I'm stressing the "as possible" because obviously if two components need to share styles then you will need to extract them out. How? Like you do any data in clojure.

(def styles {:style {:color "red"}} )

(defn some-componet

[:p styles "hi"])

(defn another-componet

[:p styles "hi"])

If your a Clojure developer by trade this is great, because i don't have to use CSS less organize and compose my styles. This means you can use clojure core to compose styles. Or you can use a rules engine to trigger your html and css based on business logic. Or a proper graph database. Or what ever you think works best for your situation/business.

“It is a word. Words are pale shadows of forgotten names. As names have power, words have power. Words can light fires in the minds of men. Words can wring tears from the hardest hearts. There are seven words that will make a person love you. There are ten words that will break a strong man’s will. But a word is nothing but a painting of a fire. A name is the fire itself.”

~ Elodin, Master Namer -- from the King Killer Chronicles by Patrick Rothfuss

We all agree names are important. They help us communicate intent. That's why I'm struggling to understand why anyone would trade "font size: smaller" for "Fz-s". But that's exactly the kind of thing you will see bundled into ideas like tailwind and atomic design:

.Fz-s {

font-size: smaller;

}

Further more, this is munging the key and value together which limits composability options at this level.

From a business perspective, your now going to pay more because you need people be fluent in names used by Tailwind, Atomic design, BEM etc... instead of the much larger pool of people that know CSS. Why? Those aren't style guides. Those are tools to help you overcome css limitations, limitations which are constantly changing. Limitations many of which we can use cljs for! The concerns these frameworks are really helping with are completely orthogonal to obscuring names. You can and should avoid doing this.

In brief, my current recommendation is that you abstract your application at as high a level as you can and no higher. That could be a set of css data or a component that is a combination of css, js, html and maybe a business query. Uniformity isn't a goal, neither is control. I see this mistake so often, the structures we build to protect us become a prison.

When you can, prefer local state/inline styles. It's state that only impacts a small area and extract that outward as necessary and aggressively.

That means using the style tag where you can't use the style attribute, elsewhere. Real companies with highly paid css specialists are doing this. Even better if you can use an amazing language and it's ecosystem to organize your css. You want to better management over css? Maybe consider a database to manage it. In memory, cached, synced the the server. One powered by differential dataflow so that it knows exactly what html, and css is needed to fulfill the smallest change the user makes and sends only whats necessary.

In short, there is no conclusion, only more questions only more options. Pick them up as needed to server your purposes.